Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758)

Table of Contents

|

| Photograph: Jonas Hansel |

Introduction

Geckos are one of the most successful lizards around today. From Gekkonidae alone, nearly 1200 species have been described, and they range throughout subtropical and tropical regions, stretching even into temperate zones (Vitt & Caldwell, 2009). In Singapore, at least 15 species of gecko have been recorded (Ng et al., 2011). Among these, the Tokay Gecko is one of the largest and is also one of the most distinctive. This gecko is also the best known species in the group, and studies on it have contributed much to our knowledge of general reptile biology (Rosler, 2011).

|

| Tokay Gecko on wall. Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

Etymology

The Tokay Gecko gets its name from the mating calls it makes - a series of characteristic 'to-kay' or 'geck-oh' sounds. In fact, the scientific name, Gekko gecko, also comes from the calls it makes.

Distribution

The Tokay Gecko has a geographic distribution extending from Eastern India, Nepal, Bangladesh, east to Southern China and South-east Asia, to the Philippines. It has also been introduced into Florida, Hawaii, Martinique in the West Indies, and Madagascar (Das, 2001). It is unclear if the lizard is native to Singapore, though it has been suggested that it probably is not (Flower, 1899). This gecko is uncommon in Singapore (Lim & Lim,1992).

View Gekko gecko distribution in a larger map This map shows the distribution of Gekko gecko in Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and their adjacent archipelagos (from Grismer, 2011)

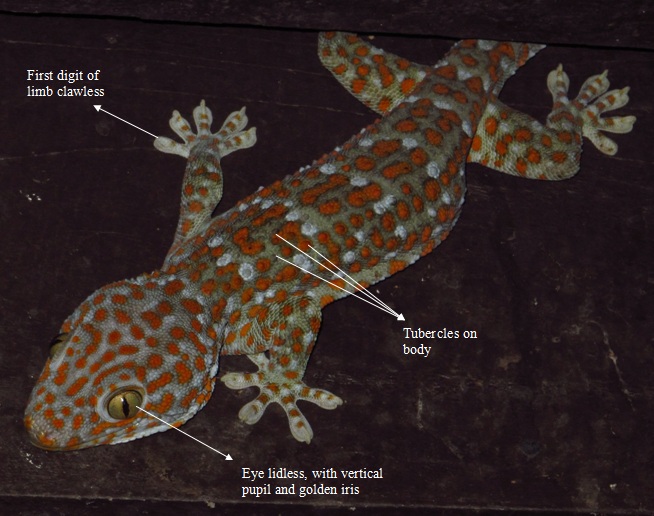

Diagnosis

(Extracted from Grismer, 2011)| Diagnostic characters |

|

| - Adult Tokay Geckos can reach 185mm SVL (Snout-Vent Length) in size; males are bigger than females - Absence of eyelids - Vertical pupils - Large, low, conical, smooth tubercles extending from nape and side of head to base of tail - 9-18 dorsal longitudinal rows of tubercles on body - Tubercles on limbs |

- First digit of limbs clawless - 10-24 pore-bearing, contiguous, precloacal scales in males - Tail with swollen base in males, due to the presence of hemipenes - Large, orange spots on dorsal surfaces of head, body, limbs and tail (Look at coloration section below) - Iris golden, copper, brown or olive - No skin flaps - Undivided, subdigital lamellae expanded through length of digit - 17-24 subdigital lamellae on fourth toe |

|

| Foot of a Tokay Gecko, showing the subdigital lamellae. Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

|

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

|

| Picture:Toh Ching Han |

|

| Pore-bearing pre-cloacal scales in males. Photograph: Charles Thompson |

Coloration

Tokay Geckos exhibit great variation in color in the wild, and are known to match their body color with the substrate they are on. The time of the day can also lighten and darken

color patterns considerably. Even the usually conspicuous orange spots may be hard to observe in these instances.

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

Where it is found near human settlements, the body is a slaty-grey or bluish-grey.

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

| Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

Biology

Habitat, diet, and behavior

The Tokay Gecko is primarily a forest gecko with an arboreal lifestyle (Das, 2011), but it is also closely associated with human settlements (Grismer, 2011). It is a nocturnal species and has been documented to feed on insects, spiders, other geckos, and even small mammals and birds (Flower, 1899). It tends to be a sit and wait forager, though it will be more active if prey abundance is high (Aowphol, 2006). It is a highly territorial species and will not hesitate to bite when threatened. When Tokay Geckos bite, they clamp their jaws in earnest and will hold on for an extended period of time (look at video below). The Tokay Gecko's defensive display involves gaping jaws which are often accompanied by warning 'barks'. Tokay Geckos also moult to grow bigger, and shedding cycles are shorter if the surrounding temperature is higher (Chiu and Maderson, 1980).

|

| Defensive display. Photograph: bsmith4815 |

| Tokay Gecko with a mouthful of winged insects. Photograph: Mary-Ruth Low Ern-Lyn |

Credits: Richard Ling

Tokay Geckos are vocal reptiles. During mating season, which can last for 4-5 months, male Tokay Geckos call to attract mates. The advertisement calls of male Tokay Geckos

consist of 2 phases. The first consists of 2-3 rattles of increasing intensity, followed by the second phase which comprises 4-11 binotes (Tang et al., 2001). The advertisement

calls show ''diel cycles and seasonal variations'', increasing in mating season and in ''parallel with the rise in androgen levels and gonadal masses'' (Tang et al., 2001). During mating, the male bites the female in the neck, holding her in place. After copulation, the female finds a suitable place to lay her clutch of 1-2 hard-shelled eggs. The eggs are glued to hard substrate such as wood and stone (Rosler, 2011). The mating pair will guard the eggs till they hatch.

Lifespan

A Tokay Gecko typically lives for an average of 10.5 years. However, in captivity, Tokay Geckos can live for much longer.

Remarkable Adaptations

Tokay Geckos have the ability to walk on different surfaces. A closer look at the gecko's foot reveals a structural hierarchy consisting of subdigital lamellae, setae and spatulas. It is postulated that the adhesion provided by the numerous spatulas works primarily through van der Waals forces (Autumn et al., 2002), and capillary forces (Huber et al., 2005).

Tokay Geckos also have the ability to shed their tails through a process known as autotomy. This serves to distract or confuse potential predators and allows time for the gecko to escape. The gecko then regenerates its tail.

Anthropic association

Pet Trade

Tokay Geckos are popular among reptile owners because of their striking coloration. However, owing to their tenacious nature, it is not recommended as a pet for rookie reptile owners, or owners who prefer to handle their pets.

Tokay Geckos as medicinal ingredients

|

| Tokay Geckos in market, Singapore. Photograph: Kat Ryan |

In China and throughout South-east Asia, Tokay Geckos are hunted for medicinal

purposes. The whole animal is stretched out and pinned for drying after the animal

has been gutted. In Singapore, it is also possible to see dried Tokay Geckos for sale in traditional Chinese medicine stores and markets. Recently, there has been a boom in the illegal trade of Tokay Geckos across South-east Asia because of an unfounded claim that the Tokay Gecko can cure AIDS.

Tokay Geckos as a symbol of luck

In Thailand, people regard the cry of the Tokay Gecko as a sign of good fortune. When the Tokay Gecko calls during the birth of a child, the people regard it as a blessing (Badger, 2006). Indeed, the more times the gecko cries, the better.

Conservation status

IUCN Red list status: Not evaluated

Taxonomic Information

| Linnaen Classification Animalia Chordata Reptilia Squamata Sauria Gekkonidae Gekko Type information When an organism is first described by a taxonomist, the physical specimen that is used is known as a holotype. The holotype and the description based on this holotype are important, because they would be used by other taxonomists in the future to identify if what they have discovered is a new species. Type locality: ''Indiis'' in error, ''Java'', Indonesia designated by Mertens (1955) The Tokay Gecko was first described by Carolus Linnaeus in his work, the Systema Naturae, page 205. Click here to access it. |

Synonyms (different names given to the same species) (obtained from Encyclopedia of Life website) Each binomial name is followed by the author's name and year described. Lacerta gecko Linnaeus, 1758:205 Gekko verticillatus Laurenti, 1768 (fide Taylor, 1963) Gekko teres Laurenti, 1768 Gekko aculeatus Houttuyn, 1782 (non Gecko aculeatus Spix, 1825) Gekko perlatus Houttuyn, 1782 Gekko guttatus Duadin, 1802 Gekko verus Merrem, 1820:42 Gekko annulatus Kuhl, 1820:132 Gekko reevesii Gray, 1831 Platydactylus guttatus Duméril & Bibron, 1836:32 Gekko tenuis [Hallowell, 1857] Gekko indicus [Girard, 1858] Gymnodactylus tenuis Hallowell, 185, Boulenger, 1885:22 Gekko verticulatus [sic] Boulenger, 1885:183 Gekko verticulatus [sic] Boulenger, 1894:82 Gekko gecko Barbour, 1912 Gekko verticillatus De Rooji, 1915:56 Gekko gecko Taylor, 1963:799 Gekko gecko Kluge, 1993 Gekko gecko Rösler, 1995 Gekko gecko Manthey & Grossman, 1997:231 Gekko gecko Cox et al., 1998:82 Gekko gecko Ziegler, 2002:165 |

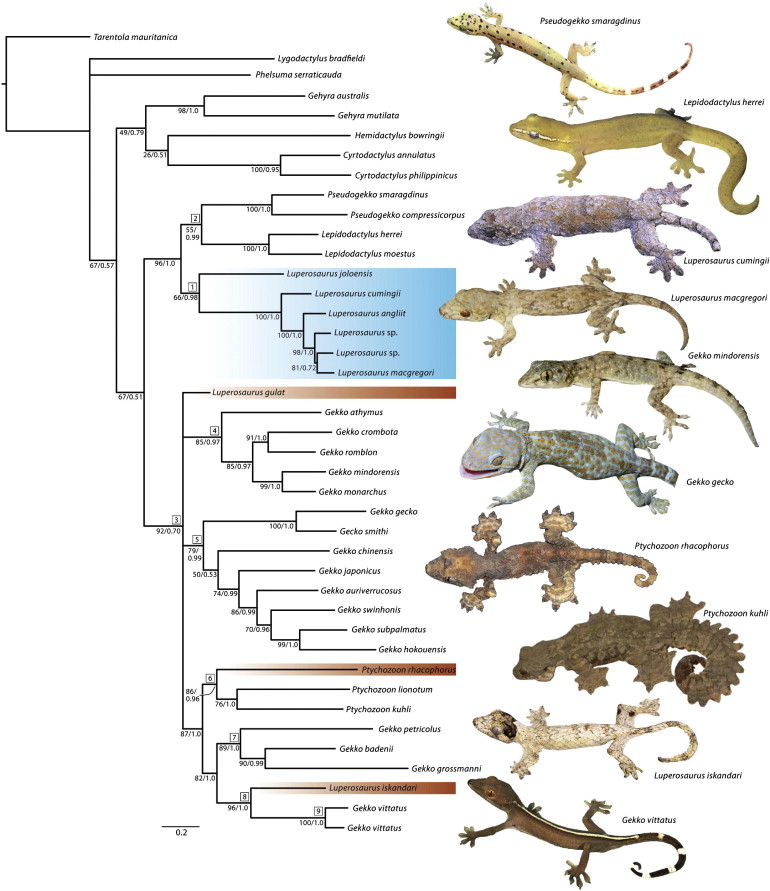

Phylogeny

|

| Abstracted from: Brown et al., 2012. Testing the phylogenetic affinities of Southeast Asia’s rarest geckos: Flap-legged geckos (Luperosaurus), Flying geckos (Ptychozoon) and their relationship to the pan-Asian genus Gekko. (Permission pending) |

The phylogenetic tree above shows the possible evolutionary relationships of various species of gecko, as tested by Brown et al. (2012).

Useful Links

Encyclopedia of Life

Animal Diversity Web

Reptile Channel

Tokay Gecko Morphs

Wikipedia

The Reptile Database

References

Aowphol, A., Thirakhupt, K., Nabhitabhata, J., Voris, H.K. (2006). Foraging ecology of the Tokay gecko, Gekko gecko in a residential area in Thailand. Amphibia-Reptilia 27: 491-503.

Autumn K, Sitti M, Liang YA, Peattie AM, Hansen WR, et al. (2002). Evidence for van der Waals adhesion in gecko setae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 12252–12256.

Badger, D.P. (2006). Lizards: A Natural History of Some Uncommon Creatures - Extraordinary Chameleons, Iguanas, Geckos, and More. Voyageur Press, MN.

Brown, R.M., Siler, C.D., Das, I., Min, Y. (2012) Testing the phylogenetic affinities of Southeast Asia’s rarest geckos: Flap-legged geckos (Luperosaurus), Flying geckos (Ptychozoon) and their relationship to the pan-Asian genus Gekko. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 63: 915-921.

Chiu, K. W. and Maderson, P. F. A. (1980). Observations on the Interactions between Thermal Conditions and Skin Shedding Frequency in the Tokay (Gekko gecko).

Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Jul. 31, 1980), pp. 245-254.

Das, I. (2004). Lizards of Borneo: A Pocket Guide. Natural History Publications, Borneo.

Flower, S.S. (1899). Notes on a second collection of reptiles made in the Malay Peninsular and Siam. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1899:631-634.

Grismer, L.L. (2011). Lizards of Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and their Adjacent Archipelagos. Chimaira Buchhandelsgesellschaft mbH, Germany.

Huber G, Mantz H, Spolenak R, Mecke K, Jacobs K, Gorb SN, Arzt E. (2005). Evidence for capillarity contributions to gecko adhesion from single spatula nanomechanical measurements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:16293–16296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506328102.

Lim, K. P., & Lim, L. K. (1992). A guide to the amphibians and reptiles of Singapore. Singapore Science Centre, Singapore.

Ng, K.L., Corlett, R.T., Tan, T.W. (2011). Singapore Biodiversity: An Encyclopedia of the Natural Envrionment and Sustainable Development. Editions Didier Millet, Singapore.

Rosler, H., Bauer, A.M., Heinicke, M.P., Greenbaum, E., Jackman, Todd., Nguyen, T.Q., Ziegler, T. (2011) Phylogeny, taxonomy, and zoogeography of the genus Gekko Laurenti, 1768 with the revalidation of G. reevesii Gray, 1831 (Sauria: Gekkonidae). Zootaxa 2989: 1–50.

Tang, Y.Z., Zhuang, L.Z., Wang, Z.W. (2001). Advertisement Calls and Their Relation to Reproductive Cycles in Gekko gecko (Reptilia, Lacertilia). Copeia, Vol. 2001, No. 1 (Feb. 16, 2001), pp. 248-253.

Vitt, L.J. & Caldwell, J.P. (2009). Herpetology. An Introduction Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles, 3rd Edition. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

The Encyclopedia of Life, http://eol.org/pages/794412/overview. Accessed 10 November 2012.

Animal Diversity Web, http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Gekko_gecko/#geographic_range. Accessed 10 November 2012.